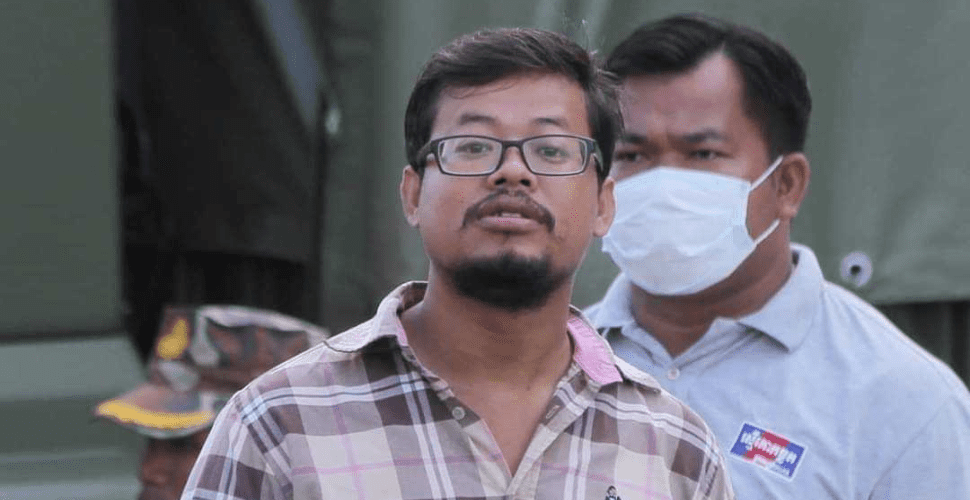

Cambodian journalist Mech Dara, who was arrested in October for exposing Cambodia's cyber-scamming compounds, was recently released following his apology to government leaders. This arrest and subsequent forced apology highlights the Cambodian government's notorious suppression of independent reporting on corruption and cyber scamming.

Dara's Arrest

In early October, the award-winning Cambodian journalist was charged with incitement to commit a felony for his coverage at the forefront of investigating the country’s cyber security compounds. Dara was released on bail on the 24th of October following 3 weeks in jail and having provided a video apology to Cambodia’s former Prime Minister, Hun Sen, and to his son, the current Prime Minister, Hun Manet. The apology video saw Dara state that he “conveyed false information that affected the leaders of the country’s reputation.”

Dara’s arrest stems from his reporting on the rise in industrial-scale scamming operations in Cambodia in recent years. This investigative work saw Dara receive a hero award from the United States Secretary of State Anthony Blinken in 2023 reflecting his vital role played in bringing this issue to light.

The Complexity of Cyber Crime:

The industrial scamming compounds are both new and innovative means for organized crime groups to expand operations. Interpol’s general secretary, Jurgen Stock, identified that cyber slavery in the region contributes between $2 and $3 trillion of illicit global financial flows. This staggering estimate provided by Interpol is further exacerbated by the United States Institute of Peace, which estimates $12.5 billion of this is funneled into Cambodia alone, contributing to nearly half of the country’s GDP. This illicit industry is transforming Cambodia into a hotspot for organized crime networks and is evolving into an inherently complex sandbox between technology, human trafficking, and illicit economies.

Young and opportunistic migrants seeking the promise of a better life through entry-level data jobs have been lured into the hands of Chinese criminal syndicates across Southeast Asia. Promising lucrative entry-level data jobs, these opportunities are heavily advertised on platforms like WeChat, Telegram, and WhatsApp. Migrants, many from poorer backgrounds, are drawn by salaries purportedly 10 times higher than what they could earn at home. However, upon arrival, these economic migrants find themselves trapped in scamming compounds, unable to escape and forced to work long to meet a daily quota or face beatings and torture.

One location of note that is tied to these operations is the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone (SSEZ) in Cambodia, established as part of the Belt and Road initiative. SSEZ is a joint Chinese and Cambodian economic development and aims to provide a platform for multinational investment into the region.

Originally established in 2006, SSEZ sought to provide support functions for 300 enterprises to settle in the region and employ between 80,000 and 100,000 industrial workers. SSEZ saw a dramatic transformation, becoming a gambling holiday hotspot for Chinese businessmen with proximity to beaches and the development of grand hotels and casinos. However, legislative loopholes and the COVID-19 pandemic shut down tourism in the city, allowing scamming operations to move into these unoccupied buildings and operate in the seemingly legitimate online gambling sector, thereby blending into Cambodia's struggling economic landscape.

What You Need to Know

The illicit activities centered around these compounds highlight the chilling evolution of modern-day slavery; victims are trafficked, coerced, and trapped within highly measured environments. These victims stem predominantly from various parts of Asia; countries of note include China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, but there are also first-hand reports to include victims from Russia and Georgia. A common tactic to maintain power over these victims is the use of physical violence, such as torture and sexual assault, punishing and motivating those who fail to meet their daily scamming quota.

Survivors report having been held in compounds under extreme conditions, with armed guards securing exits and barred windows preventing escape from the lower floors. These compounds are primarily concentrated within the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone (SSEZ), which masks its operations under the legitimate façade of online gambling and cryptocurrency sectors. Conservative estimates suggest that each office building contains approximately 1,000 victims, with offices packed with individuals, all of whom are forced to scam and lure potential victims into these compounds.

This exploitation of victims is not only physical but also psychological; this is achieved through a process known as debt-bonding used as a means of further entrapment. A fictional debt is imposed upon the victims, which includes charges for accommodation, food, trafficking transportation, and other basic fees such as the "use of a keyboard" and "air breathing”. This debt compounds over time, and those that underperform are sold to other scamming compounds for prices as high as $25,000. This burden of debt ensures the individuals who join voluntarily are prevented from leaving, becoming de facto slaves in these operations.

Although many victims are trafficked and lured to work in these compounds, there is also a portion of these individuals who join these operations willingly, attracted by the promise of high salaries. These workers may have been lured by the promise of making incredible amounts of money; however, the debt-bonding system entraps these individuals in a cycle preventing them from escaping. This distinction between voluntary workers and enslaved victims becomes incredibly blurred as both are exploited under the same system.

A Complex and Challenging Industry to Combat

The illicit cyberslavery industry is a double-edged sword. On one side of the blade are the victims who are trafficked, threatened with psychical and psychological torture, and forced to commit scams. On the other hand, there are those scammed out of their life savings, targeted by those victims with language skills, particularly English speaking, as these scamming operations become more sophisticated.

This presents significant challenges for law enforcement. The mixture of voluntary workers and victims of trafficking complicates efforts to combat these scamming compounds. Furthermore, the potential of vast profits generated by this industry has created a system that allows criminals, human traffickers, and complicit governmental officials to allow the trade to flourish. As long as these operations remain economically viable for the criminal syndicates and the corrupt government officials, ending this form of modern-day slavery will require significant international action and changes to legislation regarding cyber security and protecting those vulnerable to these scams. Particularly within Cambodia, Chou Bun Eng, the permanent vice chairwoman of Cambodia’s National Committee for Counter-Trafficking (NCCT), is on record stating that 80 percent of reported cases of human trafficking are false. This highlights the challenges that forces within Cambodia face in conjunction with the suppression of journalists such as Mech Dara and the recent forcible closure of ‘Voice of Democracy,’ an independent local news outlet that reported on this story.

Until international governments, NGOs, and law enforcement agencies coordinate efforts to address both the root causes of this trafficking and the demand for cyber labor, scamming compounds will continue to entrench themselves within the region’s illicit economy. Both the victims and targets of these scams suffer, while the criminal organizations behind these operations continue to prosper on a massive scale. With the prosecution of Dara and the suppression of the media reporting on this issue, the estimated 100,000 cyber slaves within Cambodia will continue to suffer and commit scams on an immense scale.

Discussion