MAY 1961: A naval aircraft towing an aeromagnetic survey reported the sighting of an abandoned Soviet drifting ice station, which was a semi-permanent structure built on the Arctic ocean for the use of research and espionage. Shortly after, the Soviets released information stating that they were compelled to abandon this station due to the deterioration of the ice runway used to supply it. The visage of an abandoned Soviet research piqued the interest of the Office of Naval Research (ONR), who were attracted to the idea of comparing the research technology between US drifting ice stations and those of the Soviet Union. The real question the ONR had: how to get to the abandoned station.

ROBERT FULTON

Robert Edison Fulton Jr., born April 15, 1909 was an American inventor, author and adventurer. In addition to his numerous patents, Fulton was known for traveling to 32 countries in 17 months on motorcycle in 1932. After the eruption of WWII in 1939, Fulton started work on a gunnery simulator to train pilots in aerial combat. In May of 1942, Fulton had the opportunity to demonstrate his training device to Commander Luis de Florez, who was in the process of developing the US Navy’s Special Devices Division. De Florez was interested in Fulton's device and eventually, the Navy purchased 500 trainers at a price of $6 million. Including a gunnery manual developed by Fulton, his device became the Navy’s chief simulator for the education of air-to-air combat.

After WWII, Fulton purchased 15 acres of land neighboring an airport in Danbury, Connecticut as his home base, building a home and workshop on the parcel of land. He devoted the majority of his time and left over capital to the development of a flying car. He built and tested 8 versions of his automobile before running out of funds to continue the project. While flight testing his automobile, Fulton wondered what the outcome may be if he had been forced to land his aircraft in inaccessible terrain. This question sparked the development of the Skyhook system.

THE SKYHOOK SYSTEM

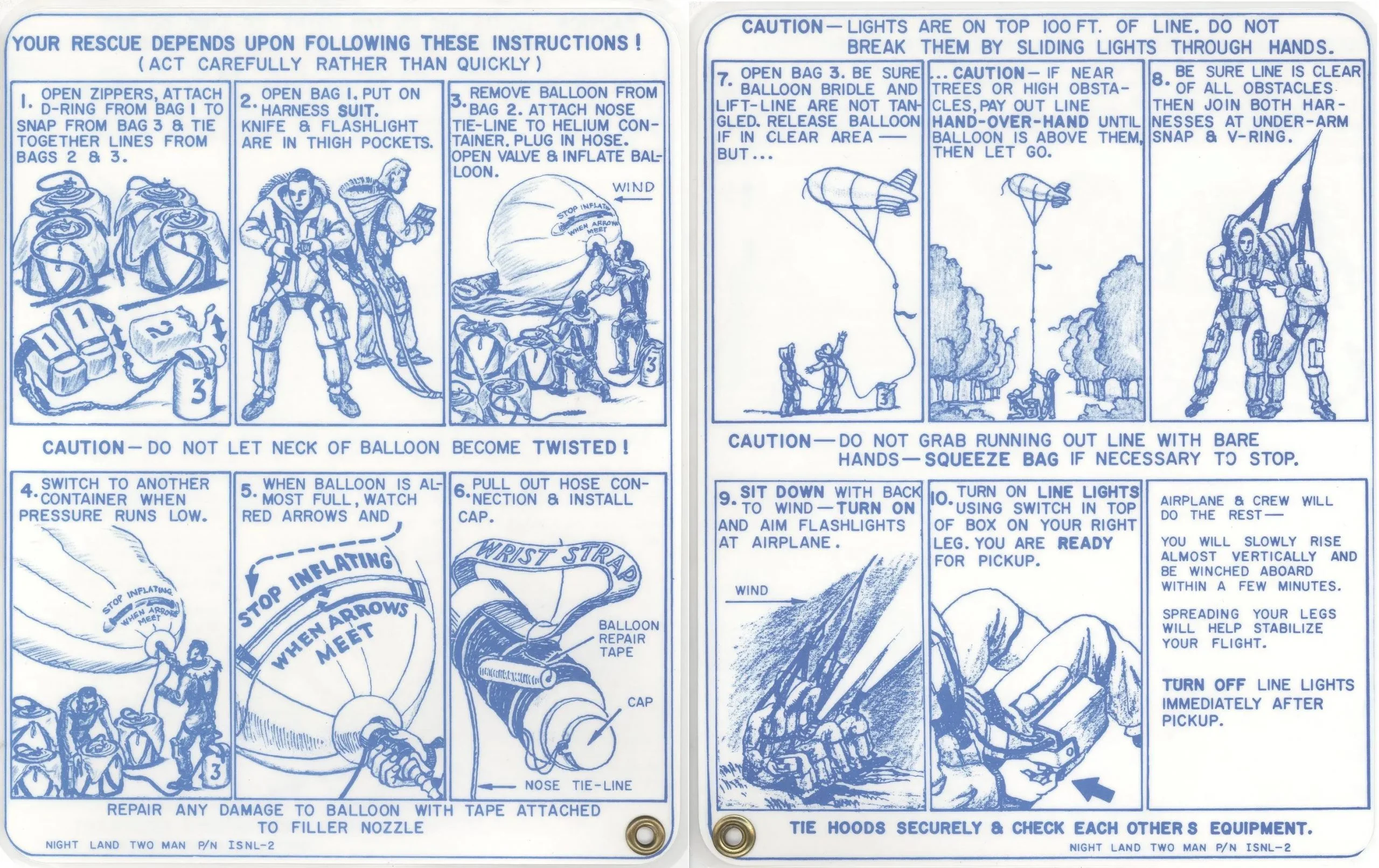

The Fulton aerial retrieval system, colloquially known as the Skyhook, was fitted with a harness that was attached to extra-tough, braided nylon rope around 500 feet long. This system could be used to retrieve either people or cargo, depending on the mission. A portable container of helium was attached and used to inflate a blimp-shaped balloon, which allowed the rope to rise to its full height before retrieval.

The aircraft fitted for pickup was equipped with two 30-foot steel tubes protruding from its nose at a 70-degree angle. When it was time for retrieval, the aircraft would fly into the pickup rope raised by the balloon, catching the rope between the steel tubes and releasing the balloon as the line was secured to the aircraft. Once the rope had streamed under the fuselage of the aircraft, crew used a J-hook to secure the rope and a powered winch to reel the cargo or people in.

THE OPERATION

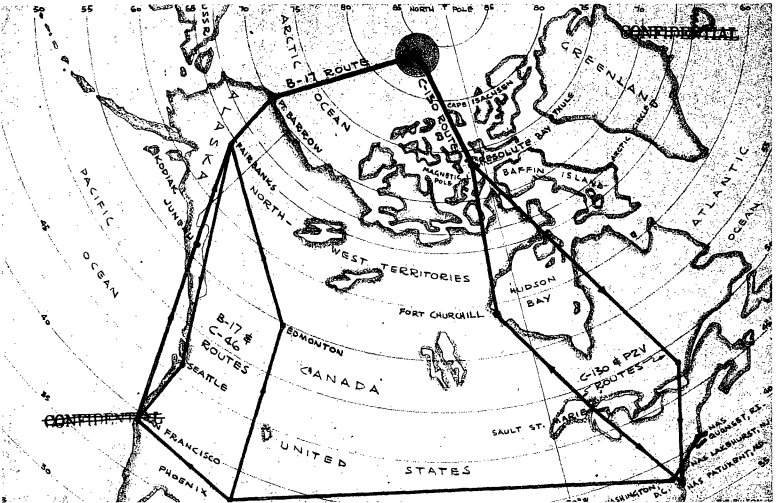

The ONR was very interested in the collection of information from station NP 9, but they were unsure of how to get there. At this time, Fulton introduced to them the Skyhook system as a solution to their problem. Soon, they began planning their mission pending the final approval of the Chief of Naval Operations. The operation was scheduled for September due to still having ample daylight and decent weather, as well as station NP 9’s 600-mile proximity at the time to the US Air Force base in Thule, Greenland. This is where the operation would be launching from. Unfortunately, due to approval taking longer than anticipated, issues with equipment testing, and the unfulfilled promise of a support aircraft for the mission, the ONR was forced to halt planning. This was until March of 1962, when a new avenue presented itself.

Mission planners had received word that the Soviets had abandoned a different drifting ice station, NP 8, abruptly and unexpectedly due to a pressure ridge destroying its ice runway. This drifting ice station was in a more accessible positon for the ONR, and was more up-to-date as well. In mid-april of 1962, The ONR requested the use of a Royal Canadian Air Force base at Resolute Bay, approximately 600 miles from NP 8 for the mission, which the Canadian government agreed to. Once the logistics were set up, it was time to search for NP 8. A C-130 flew to NP 8’s last known location, then executed a box search at 10-mile intervals. This search turned up with nothing but ice, so they began searching at 5-mile intervals the next day. This also failed to provide a current location of station NP 8. For the time being, the ONR called off Operation COLDFEET.

On May 4th 1962, a reconnaissance aircraft spotted station NP 8 well to the east of its anticipated location. While the ONR had held out hope that the mission could still work, funding for the mission had run dry. Eventually, requests for funding went to the intelligence community, many entities of which had expressed their interest in COLDFEET. Apparently, Robert Fulton had been working with the CIA on the development of his Skyhook system since the fall of 1961. He had also been working with Intermountain Aviation out of Arizona to equip a B-17 with the Skyhook gear around that same time. Over a few months after equipping the gear, Intermountain Aviation pilots flew a multitude of practice missions with the gear to perfect infiltration and extraction using the Skyhook. Fulton had then pitched Intermountain Aviation the idea of participating in COLDFEET, to which they agreed. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) then proceeded to contribute $30,000 to the mission, with Intermountain Aviation contributing their Skyhook-furnished B-17 and a C-46 as a support aircraft for the mission.

After an additional change of location to Point Barrow due to a delay in receiving necessary diplomatic access from the government of Canada, the B-17 and C-46 reached their launch point on May 26th, 1962. The next day, the B-17 flown by CIA-contracted pilots Connie Seigrist and Douglas Price began their search for station NP 8. After 13 hours with no results, the pilots decided to return to Point Barrow. On May 28th, 1962, Seigrist and Price found the location of NP 8 with the assistance of a Navy P2V Neptune long-range patrol aircraft. After circling the station to determine a drop off point, Major James Smith of the US Air Force and Lieutenant Leonard LeSchack of the US Naval Reserve parachuted onto the thick ice below. Once supplies were dropped to Smith and LeSchack and a favorable report was received from Smith via the radio, the pilots and crew departed.

Smith and LeSchack were allotted 72 hours from time of drop off to explore the drifting ice station. While they explored, the pickup equipment was installed on the B-17 and practice pickups were conducted. When it was time to pick up the investigators, weather made it hard to locate station NP 8, and the B-17 was forced to return to Point Barrow after 2 futile searches. On June 1st of 1962, assistance was asked of the Navy’s P2V again and NP 8 was quickly located. It was now time for the pickup.

Despite the less-than-ideal weather and wind conditions, the pilots managed to line up their aircraft with the Skyhook’s mylar markers. The cargo, a 150-pound canvas bag of documents, exposed film and equipment sampled, was picked up with little to no difficulty. When it came to Smith and LeSchack’s pickup, conditions seemed to worsen. The wind was blowing hard, making it difficult for the investigators to stay grounded as their balloons inflated before pickup. Eventually, both Smith and Leschack were safely lifted off the ground and winched into the aircraft.

THE OUTCOME

The cargo collected during Operation COLDFEET produced intelligence that confirmed to the ONR that the Soviet Union had gained a superior understanding of polar meteorology and oceanography than the United States. The ONR also learned that station NP 8 was established to permit long periods of silent operation, confirming the significance of acoustical work and underwater signal research to the Soviet Union. According to the ONR, Operation COLDFEET was a resounding success despite its complications and even under harsh weather conditions, the pickup of both the cargo and investigators was made in its best time yet (6.5 minutes). Robert Fulton's Skyhook system continued to be used in future operations, and was additionally depicted in 1965 James Bond film Thunderball.

Discussion