Earlier this month, the Department of Defense (DoD) confirmed a 17-day airspace incursion by multiple unidentified aircraft over Langley Air Force Base (AFB) in Hampton, VA, last December. Langley AFB, home to the F-22 Raptor, is situated near Naval Station Norfolk, the base for Virginia-class submarines. The aircraft were observed by military personnel, mainly just after sunset, traveling at an estimated speed of 100 MPH through restricted military airspace. This event is just the latest of several reports from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the DoD, and officials are working to determine how to prevent such incursions and safeguard domestic operations from aerial threats.

Understanding Airspace Restrictions

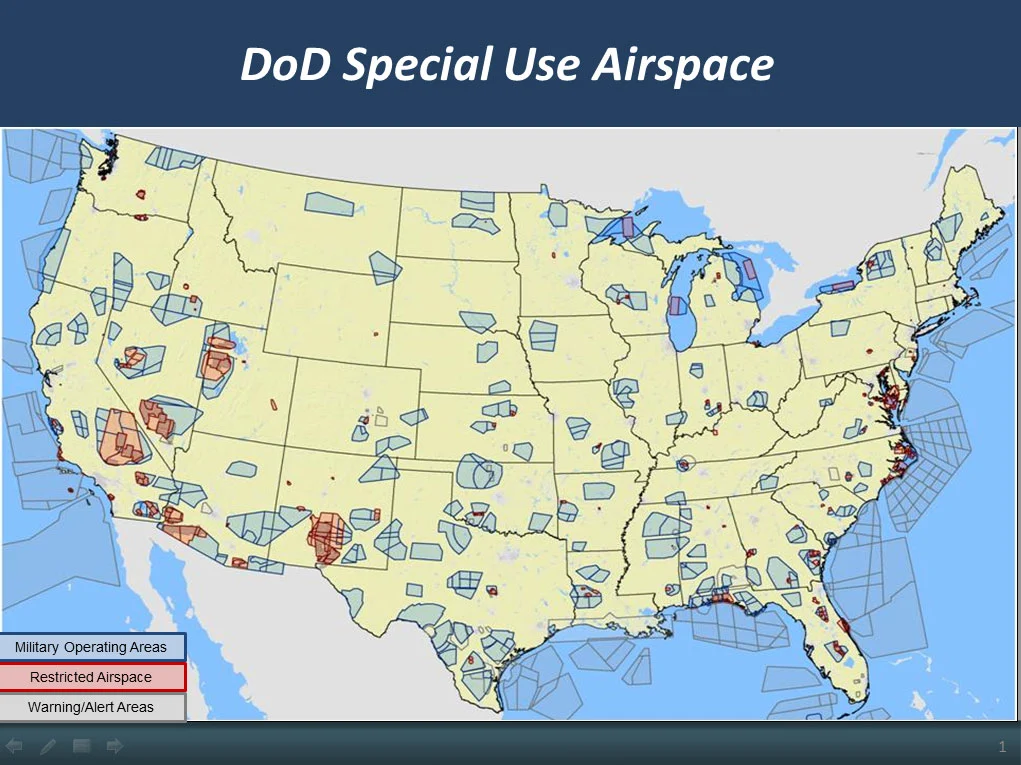

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has categorized certain airspace over National Defense Installations and high risk areas as 'restricted airspace.' The DoD and FAA have designated certain airspaces as "Military Operating Areas" (MOAs), which, while not directly over military installations or high-priority areas, restrict the types of aircraft permitted to operate within these zones. The FAA authorizes these airspaces for long—or short-term periods and generally reserves them for training U.S. military pilots and to restrict air traffic from operating near national security areas. The FAA strictly prohibits commercial and private aircraft, manned or unmanned, from operating inside of MOAs without express permission from the DoD or FAA.

The FAA can also authorize temporary flight restrictions (TFRs), a common practice employed by the U.S. Secret Service (USSS) when protectees are in areas where small unmanned aerial vehicles (sUAVs) typically have minimal restrictions on flying. During a TFR, no aircraft, including drones, are permitted to fly, which greatly assists in reducing the amount of potential aerial threats. TFRs create a secure aerial "bubble" around protected spaces, helping military and law enforcement identify hostile intent when aircraft enter the restricted area. Examples of other restricted airspaces include those over the White House, the Pentagon, Capitol Hill, and national defense installations.

Drones Incursions: A Growing Trend

The Langley AFB incident marked the first in a series of incursions that have repeatedly occurred on U.S. soil in recent years. This event was the largest publicized drone incursion in terms of volume within a single time frame at a national defense installation. For 17 days, U.S. Air Force General Mark Kelly received reports and experienced first hand these drones entering the bases restricted airspace. Kelly, an experienced fighter pilot, estimated the drones flew approximately 3,000 to 4,000 feet and sounded like a "parade of lawnmowers." Kelly reported these incursions to the Pentagon where they would eventually land directly on President Biden's desk at the situation room. The only response was to cancel nighttime missions and move the F-22 to a different base.

In January 2023, an F-16 Fighter Jet collided with a drone within the MOA of the Barry M. Goldwater Range southwest of Phoenix. The DoD reported the jet struck the drone near the canopy but took no damage and landed safely in Tucson. As illustrated in the image above, a significant portion of southern Arizona's airspace is designated as restricted; yet, over 22 airspace violations were reported between October 2022 and June 2023. Speculation surrounding the origins of these drones range from cartel activity to state-sponsored foreign spies collecting on U.S. military operations. The origin of the drone which struck the F-16 has not been confirmed.

A separate event occurred in January 2024 involving a drone being operated inside the Newport News Shipyard and BAE Systems in Norfolk, Virginia, by Fengyun Shi, a Chinese Graduate Student from the University of Minnesota. Shi's drone became stuck in a tree and was later recovered by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), revealing several images and videos of the shipyard. Shi was arrested on January 18th before he could board a one-way flight to China. The Department of Justice later sentenced Shi to 6 months in federal prison after he pled guilty to two misdemeanor counts of the use of an aircraft for the unlawful photographing of a designated installation without authorization. Shi maintained during his plea arrangement that the images taken by the drone were not for malicious use and were only recreational.

A drone was also at the forefront of the recent assassination attempt of Former President Donald Trump at a Rally in Butler, PA on July 13th. The would be assassin, Thomas Crooks, used a drone hours before Trump ever took stage and surveilled law enforcement positions before shooting the former president. According to a report from the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, a limited two hour TFR was in place for the Trump rally, from 4:15 p.m. through 6:15 p.m. The TFR went against the wishes of the c-UAS (counted unmanned aerial systems) Secret Service agent testifying to the committee, who reportedly requested and extended TFR due to Trump taking the stage late, but the request was denied. Crooks reportedly flew his drone for 11 minutes beginning at 3:51 p.m. over the rally area. The USSS agent testified his UAS detection equipment was 'malfunctioning' while Crooks was operating the drone and throughout the rally. It remains unclear whether the drone usage aided Crooks in selecting a location. Nevertheless, it is still a considerable security breach that a drone was operated in one of the biggest presidential security lapses since Ronald Reagan.

Domestic Drone Defense: What Can Be Done?

The primary challenge for domestic military installations attempting to intercept these drones is the Posse Comitatus Act (18 U.S.C. § 1385), which restricts the federal government from using the military to enforce domestic laws within the United States. While installation commanders and troops still have the inherent right to self-defense, there is not an immediate threat to life with drones flying in restricted airspace. This effectively hampers the military's ability to respond to drones flying over installations, requiring them to wait until the drone leaves the airspace and hoping that local law enforcement can track it down and identify its origin. This does not mean that federal agencies, such as the FBI, cannot intercept these drones if they are present. However, the likelihood of an FBI agent or other federal agent being in the right place at the right time to intercept these drones is quite low.

Drones flying over TFRs or MOAs (such as a political rally) can be intercepted by local, state, or federal authorities for the purpose of identifying their source, provided the authorities are within their jurisdiction to enforce the law. Homeland Security Advisor Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall convened a brainstorming session at the White House, which led to multiple concepts on how to handle the threat of drones. These concepts ranged from directed energy lasers to GPS jamming equipment and Very High Frequency (VHF) jammers. However, if misdirected, these technologies could pose unnecessary risks to commercial aircraft or disrupt Wi-Fi and emergency communication signals. Additionally, there were suggestions to use net capturing devices and deploy other drones to knock them out of the sky.

NDAA 2025

The U.S. military is currently training its troops in c-UAS operations, utilizing various detection and jamming equipment. However, troops currently lack the authority to take action within U.S. national airspace. The current proposed National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2025, presented by the Senate Armed Services Committee, outlines key areas of significant importance to the security of the Armed Forces. The proposed NDAA requires the formation of a counter-uncrewed aircraft system task force to evaluate existing guidance and formulate strategies for addressing drone technologies. It directs the Army, Navy, and Air Force to brief on their c-UAS plans and requires a report on findings from the DOD's counter-UAS Cross-Functional Team. Additionally, the Act authorizes increased funding for counter-UAS research and combatant command activities, mandates a full-scale exercise in DOD airspace, and emphasizes developing secure domestic supply chains for small UAS components. Collectively, these actions are designed to improve the military's ability to handle drone threats efficiently and safeguard U.S. airspace.

Discussion