President Donald Trump escalated his public push for lower interest rates ahead of next week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting, telling reporters after a Thursday walkthrough of the Federal Reserve’s renovation site in Washington that “rates have to come down—fast.” He has repeatedly urged Chair Jerome Powell to cut the federal‑funds rate by at least three %age points, calling the current 4.25%–4.50% target range “an anchor on housing and growth.” Senior aides backed him up: Budget Director Russell Vought argued that every %age‑point reduction would shave roughly $365 billion from annual federal interest costs, while Deputy Chief of Staff James Blair described the Fed’s wait‑and‑see posture as “indefensible,” especially with tariff‑driven price shocks still working through supply chains.

Renovation Tour and On‑Camera Clash

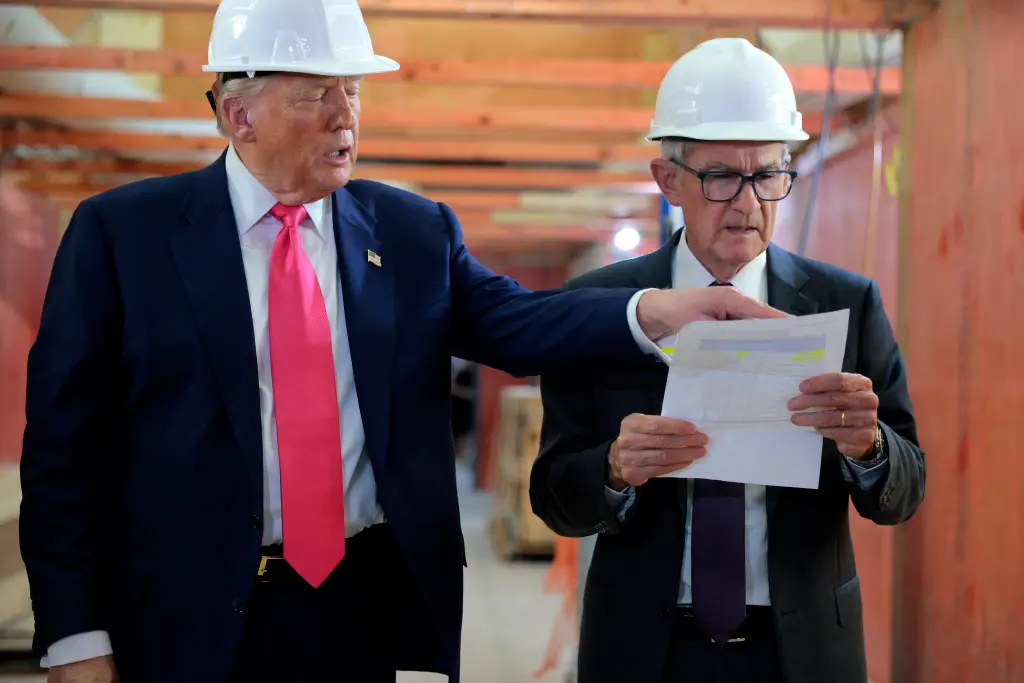

Trump pressed his case during a rare presidential visit to the Fed’s headquarters, now in the middle of a multibillion‑dollar overhaul. Wearing a hard hat and flanked by Powell and Senator Tim Scott, the president asserted that the central bank’s renovation costs had ballooned far beyond the official budget. Powell countered that the larger figure Trump cited bundled in a separate building finished years ago, and said the current project remains within the scope the Board approved. Cameras caught an awkward exchange: Trump handed Powell a sheet of numbers while repeating his demand for aggressive rate cuts; asked how he would treat a project manager who overshot costs in his real‑estate days, he replied, “I’d fire ’em,” then added that he “didn’t want to be personal.”

Renovation overruns—real or perceived—have turned into a political cudgel. The White House says the episode shows the Fed’s “mission creep” and weak internal controls. Powell’s team counters that post‑9/11 security standards, blast‑resistant windows, asbestos abatement, and higher prices for steel and glass explain the budget pressures. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has encouraged the Fed’s inspector general to review the renovation in detail, and Senate Banking Chair Tim Scott has asked for a full accounting of change orders and contingency funds.

Powell’s Response and Central‑Bank Independence

Powell kept to script, reminding reporters the Fed is in its pre‑meeting blackout and declining to discuss specifics. He told colleagues afterward that the Committee will “act based on data, not deadlines.” Inside the central bank, there is broader concern that a presidential visit to the building—paired with direct, televised pressure—could undermine the perception of independence if investors begin to believe policy is being set at the White House rather than Constitution Avenue.

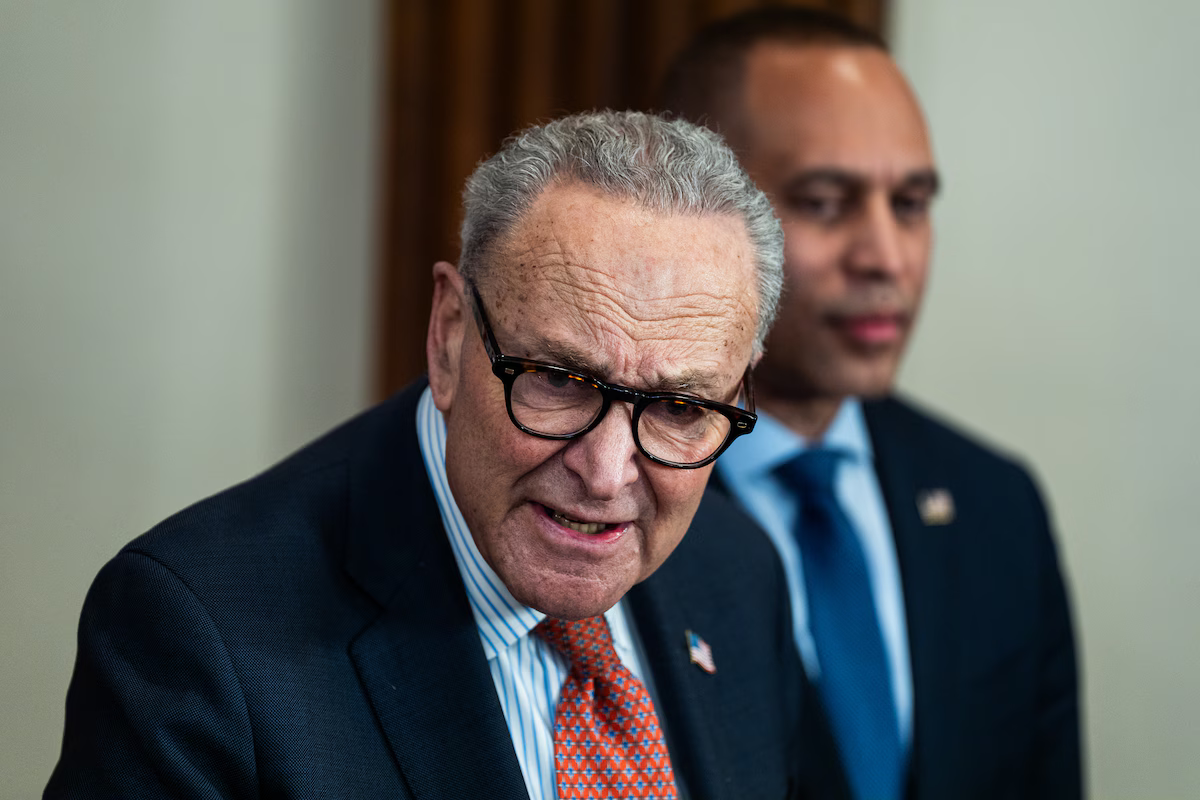

Trump said he has “no plans right now” to remove Powell before his term ends in May 2026, but added, “I believe he knows what the right thing is.” Lawmakers split along familiar lines. Republican hawks argue the tariff regime will slow growth and justify an immediate cut. Democrats say overt jawboning risks credibility damage, though few are proposing new statutory firewalls between the Fed and the presidency. Economists note that presidents have leaned on Chairs before—from Lyndon Johnson browbeating William McChesney Martin at the ranch, to George H. W. Bush complaining about Alan Greenspan—but an in‑person confrontation at the Fed itself is close to unprecedented.

Economic Stakes and Market Reaction

Markets largely shrugged. Ten‑year Treasury yields nudged a couple of basis points higher after jobless‑claims data pointed to continued labor‑market resilience, reinforcing expectations that the Fed will hold steady next week. The S&P 500 finished essentially flat, and the dollar inched higher after Trump clarified he didn’t intend to fire Powell. Mortgage lenders and homebuilders cheered the pressure campaign, arguing that rates are choking off new construction and keeping existing owners “locked in” to low‑coupon mortgages, which starves supply. Regional banks were more cautious, warning that rapid cuts could compress net‑interest margins and reignite asset‑liability mismatches.

Corporate treasurers preparing fall refinancings are already gaming out scenarios with two quarter‑point cuts this year—roughly what the Fed’s June projections implied if inflation continued to drift lower. The White House, by contrast, is openly pushing for a steeper path to ease federal debt‑service costs and offset the bite of higher tariffs in consumer prices. Powell’s staff continues to frame tariffs as upside inflation risk that argues for patience, not haste.

The renovation itself has become a metaphor in the broader debate. Powell says the same inflationary forces the Fed is fighting—elevated materials costs, labor shortages, supply frictions—help explain why the price tag rose. Trump allies respond that if the Fed “can’t manage its own house,” it should err on the side of stimulus rather than risk a downturn with tight money. The inspector general’s report, due to Congress later this summer, will offer fodder to both sides depending on how it parses cost overruns versus mandated security upgrades.

What Comes Next

• July 29–30 FOMC meeting: Futures put low odds on an immediate cut. Expect Powell to emphasize data dependence, tariff uncertainties, and the need to see a clearer downtrend in core inflation.

• August: The Fed’s inspector‑general report on renovation spending lands on Capitol Hill. If it faults governance or transparency, the White House will use it to intensify pressure; if it largely vindicates the project, Powell gains some political cover.

• September FOMC: Markets see this as the first plausible window for a 25‑basis‑point reduction, contingent on softer inflation prints and signs that tariffs are curbing demand faster than they’re lifting prices.

• Powell’s tenure: As May 2026 approaches, speculation will grow over whether Trump names a successor more aligned with his rate views, or attempts to reassign Powell to a regular Board seat—an option past administrations have floated but never executed.

Trump’s hard‑hat visit to the Fed packaged two messages: rein in your construction costs and cut rates—now. Powell’s answer, delivered without fanfare, was the same one he has given for two years: watch the data.

Discussion